2. Chromatic Scale and Temperament¶

Most of us have some familiarity with the chromatic scale and know that it must be tempered, but what are their precise definitions? Why is the chromatic scale so special and why is temperament needed? We first explore the mathematical basis for the chromatic scale and tempering because the mathematical approach is the most concise, clear, and precise treatment. We then discuss the historical/musical considerations for a better understanding of the relative merits of the different temperaments. A basic mathematical foundation for these concepts is essential for a good understanding of how pianos are tuned. For information on tuning, see White, Howell, Fischer, Jorgensen, or Reblitz in the References at the end of this book.

a. Mathematics of the Chromatic Scale and Intervals¶

Three octaves of the chromatic scale are shown in the table Table 2.2a: Frequency Ratios of Intervals in the Chromatic Scale using

the A, B, C, ... notation. Black keys on the piano are shown as sharps,

e.g. the # on the right of C represents C#, etc., and are shown

only for the highest octave. Each successive frequency change in the chromatic

scale is called a semitone and an octave has 12 semitones. The major intervals

and the integers representing the frequency ratios for those intervals are

shown above and below the chromatic scale, respectively. Except for multiples

of these basic intervals, integers larger than about 10 produce intervals not

readily recognizable to the ear. In reference to Table 2.2a: Frequency Ratios of Intervals in the Chromatic Scale, the most

fundamental interval is the octave, in which the frequency of the higher note

is twice that of the lower one. The interval between C and G is called

a 5th, and the frequencies of C and G are in the ratio of 2 to 3. The

major third has four semitones and the minor third has three. The number

associated with each interval, e.g. four in the 4th, is the number of white

keys, inclusive of the two end keys, for the C major scale and has no

further mathematical significance.

Table 2.2a: Frequency Ratios of Intervals in the Chromatic Scale¶

Semitones |

Note |

Interval |

Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

C |

Unison |

1:1 |

1 |

C# |

Minor Second |

16:15 |

2 |

D |

Major Second |

9:8 |

3 |

D# |

Minor Third |

6:5 |

4 |

E |

Major Third |

5:4 |

5 |

F |

Perfect Fourth |

4:3 |

6 |

F# |

Tritone |

25:18 |

7 |

G |

Perfect Fifth |

3:2 |

8 |

G# |

Minor Sixth |

8:5 |

9 |

A |

Major Sixth |

5:3 |

10 |

A# |

Minor Seventh |

9:5 |

11 |

B |

Major Seventh |

15:8 |

12 |

C |

Octave |

2:1 |

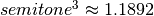

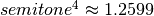

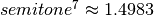

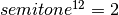

We can see from the above that a 4th and a 5th “add up” to an octave and a major 3rd and a minor 3rd “add up” to a 5th. Note that this is an addition in logarithmic space, as explained below. The missing integer 7 is also explained below. These are the “ideal” intervals with perfect harmony. The “equal tempered” (ET) chromatic scale consists of “equal” half-tone or semitone rises for each successive note. They are equal in the sense that the ratio of the frequencies of any two adjacent notes is always the same. This property ensures that every note is the same as any other note (except for pitch). This uniformity of the notes allows the composer or performer to use any key without hitting bad dissonances, as further explained below. There are 12 equal semitones in an octave of an ET scale and each octave is an exact factor of two in frequency. Therefore, the frequency change for each semitone is given by:

(1)¶

Equation (1) defines the ET chromatic scale and allows the calculation of the frequency ratios of “intervals” in this scale. How do the “intervals” in ET compare with the frequency ratios of the ideal intervals? The comparisons are shown in Table 2.2b: Ideal vs. Equal Tempered Intervals and demonstrate that the intervals from the ET scale are extremely close to the ideal intervals.

The errors for the 3rds are the worst, over five times the errors in the other

intervals, but are still only about 1%. Nonetheless, these errors are readily

audible, and some piano aficionados have generously dubbed them “the rolling

thirds” while in reality, they are unacceptable dissonances. It is a defect

that we must learn to live with, if we are to adopt the ET scale. The errors in

the 4ths and 5ths produce beats of about 1 Hz near C4, which is barely

audible in most pieces of music; however, this beat frequency doubles for every

higher octave.

The integer 7, if it were included in Table 2.2a: Frequency Ratios of Intervals in the Chromatic Scale, would have represented an interval with the ratio 7/6 and would correspond to a semitone squared. The error between 7/6 and a semitone squared is over 4% and is too large to make a musically acceptable interval.

Table 2.2b: Ideal vs. Equal Tempered Intervals¶

Interval |

Frequency Ratio |

Equal Tempered Scale |

Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

Minor Third |

|

|

|

Major Third |

|

|

|

Perfect Fourth |

|

|

|

Perfect Fifth |

|

|

|

Octave |

|

|

|

It is a mathematical accident that the 12-note ET chromatic scale produces so many ratios close to the ideal intervals. Only the number 7, out of the smallest 8 integers (Table 2.2a: Frequency Ratios of Intervals in the Chromatic Scale), results in a totally unacceptable interval. The chromatic scale is based on a lucky mathematical accident in nature! It is constructed by using the smallest number of notes that gives the maximum number of intervals. No wonder early civilizations believed that there was something mystical about this scale. Increasing the number of keys in an octave does not result in much improvement of the intervals until the numbers become quite large, making that approach impractical for most musical instruments. Mathematically speaking, the unacceptable number 7 is a victim of the incompleteness (a. Mathematics of the Chromatic Scale and Intervals) of the chromatic scale and is therefore, not a mystery.

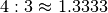

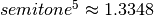

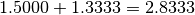

Note that the frequency ratios of the 4th and 5th do not add up to that of the

octave ( vs.

vs.  ). Instead, they add

up in logarithmic space because

). Instead, they add

up in logarithmic space because  . In

logarithmic space, multiplication becomes addition. Why might this be

significant? The answer is because the geometry of the cochlea of the ear seems

to have a logarithmic component. Detecting acoustic frequencies on a

logarithmic scale accomplishes two things: you can hear a wider frequency range

for a given size of cochlea, and analyzing ratios of frequencies becomes simple

because instead of multiplying or dividing two frequencies, you only need to

add or subtract their logarithms. For example, if

. In

logarithmic space, multiplication becomes addition. Why might this be

significant? The answer is because the geometry of the cochlea of the ear seems

to have a logarithmic component. Detecting acoustic frequencies on a

logarithmic scale accomplishes two things: you can hear a wider frequency range

for a given size of cochlea, and analyzing ratios of frequencies becomes simple

because instead of multiplying or dividing two frequencies, you only need to

add or subtract their logarithms. For example, if C3 is detected by the

cochlea at one position and C4 at another position 2mm away, then C5

will be detected at a distance of 4 mm, exactly as in the slide rule

calculator. To show you how useful this is, given F5, the brain knows that

F4 will be found 2mm back! Therefore, intervals (remember, intervals are

frequency divisions) and harmonies are particularly simple to analyze in a

logarithmically constructed cochlea. When we play intervals, we are performing

mathematical operations in logarithmic space on a mechanical computer called

the piano, as was done in the 1950’s using the slide rule. Thus the logarithmic

nature of the chromatic scale has many more consequences than just providing a

wider frequency range than a linear scale. The logarithmic scale assures that

the two notes of every interval are separated by the same distance no matter

where you are on the piano. By adopting a logarithmic chromatic scale, the

piano keyboard is mathematically matched to the human ear in a mechanical way!

This is probably one reason for why harmonies are pleasant to the ear -

harmonies are most easily deciphered and remembered by the human hearing

mechanism.

Suppose that we did not know (1); can we generate the ET chromatic scale

from the interval relationships? If the answer is yes, a piano tuner can tune a

piano without having to make any calculations. These interval relationships, it

turns out, completely determine the frequencies of all the notes of the 12 note

chromatic scale. A temperament is a set of interval relationships that defines

a specific chromatic scale; tempering generally involves detuning from perfect

intervals. From a musical point of view, there is no single “chromatic scale”

that is best above all else although ET has the unique property that it allows

free transpositions. Needless to say, ET is not the only musically useful

temperament, and we will discuss other temperaments below. Temperament is not

an option but a necessity; we must choose a temperament in order to accommodate

the mathematical difficulties discussed below and in following b. Temperament, Music, and the Circle of Fifths &

c. Pythagorean, Equal, Meantone, and “Well” Temperaments. Most musical instruments based on the chromatic scale must be

tempered. For example, the holes in wind instruments and the frets of the

guitar must be spaced for a specific tempered scale. The violin is a devilishly

clever instrument because it avoids all temperament problems by spacing the

open strings in fifths. If you tune the A-440 string correctly and tune all

the others in 5ths, these others will be close, but not tempered. You can still

avoid temperament problems by fingering all notes except one (the correctly

tuned A-440). In addition, the vibrato is larger than the temperament

corrections, making temperament differences inaudible.

The requirement of tempering arises because a chromatic scale tuned to one

scale (e.g., C-major with perfect intervals) does not produce acceptable

intervals in other scales. If you wrote a composition in C-major having

many perfect intervals and then transposed it, terrible dissonances can result.

There is an even more fundamental problem. Perfect intervals in one scale also

produce dissonances in other scales needed in the same piece of music.

Tempering schemes were therefore devised to minimize these dissonances by

minimizing the de-tuning from perfect intervals in the most important intervals

and shifting most of the dissonances into the less used intervals. The

dissonance associated with the worst interval came to be known as “the wolf”.

The main problem is, of course, interval purity; the above discussion makes it clear that no matter what you do, there is going to be a dissonance somewhere. It might come as a shock to some that the piano is a fundamentally imperfect instrument! The piano gives us every note, but locks us into one temperament; on the other hand, we must finger every note on the violin, but it is free of temperament restrictions.

The name “chromatic scale” applies to any 12-note scale with any temperament. For the piano, the chromatic scale does not allow the use of frequencies between the notes (as you can with the violin), so that there is an infinite number of missing notes. In this sense, the chromatic scale is (mathematically) incomplete. Nonetheless, the 12-note scale is sufficiently complete for a majority of musical applications. The situation is analogous to digital photography. When the resolution is sufficient, you cannot see the difference between a digital photo and an analog one with much higher information density. Similarly, the 12-note scale has sufficient pitch resolution for a sufficiently large number of musical applications. This 12-note scale is a good compromise between having more notes per octave for greater completeness and having enough frequency range to span the range of the human ear, for a given instrument or musical notation system with a limited number of notes.

There is healthy debate about which temperament is best musically. ET was known from the earliest history of tuning. There are definite advantages to standardizing to one temperament, but that is probably not possible or even desirable in view of the diversity of opinions on music and the fact that much music now exist, that were written with specific temperaments in mind. Therefore we shall now explore the various temperaments.

b. Temperament, Music, and the Circle of Fifths¶

The above mathematical approach is not the way in which the chromatic scale was historically developed. Musicians first started with intervals and tried to find a music scale with the minimum number of notes that would produce those intervals. The requirement of a minimum number of notes is obviously desirable since it determines the number of keys, strings, holes, etc. needed to construct a musical instrument. Intervals are necessary because if you want to play more than one note at a time, those notes will create dissonances that are unpleasant to the ear unless they form harmonious intervals. The reason why dissonances are so unpleasant to the ear may have something to do with the difficulty of processing dissonant information through the brain. It is certainly easier, in terms of memory and comprehension, to deal with harmonious intervals than dissonances. Some dissonances are nearly impossible for most brains to figure out if two dissonant notes are played simultaneously. Therefore, if the brain is overloaded with the task of trying to figure out complex dissonances, it becomes impossible to relax and enjoy the music, or follow the musical idea. Clearly, any scale must produce good intervals if we are to compose advanced, complex music requiring more than one note at a time.

We saw in Table 2.2a: Frequency Ratios of Intervals in the Chromatic Scale and Table 2.2b: Ideal vs. Equal Tempered Intervals that the optimum number of notes in a scale turned out to be 12. Unfortunately, there isn’t any 12-note scale that can produce exact intervals everywhere. Music would sound better if a scale with perfect intervals everywhere could be found. Many such attempts have been made, mainly by increasing the number of notes per octave, especially using guitars and organs, but none of these scales have gained acceptance. It is relatively easy to increase the number of notes per octave with a guitar-like instrument because all you need to do is to add strings and frets. The latest schemes being devised today involve computer generated scales in which the computer adjusts the frequencies with every transposition; this scheme is called adaptive tuning (Sethares).

The most basic concept needed to understand temperaments is the concept of the

circle of fifths. To describe a circle of fifths, take any octave. Start with

the lowest note and go up in 5ths. After two 5ths, you will go outside of this

octave. When this happens, go down one octave so that you can keep going up in

5ths and still stay within the original octave. Do this for twelve 5ths, and

you will end up at the highest note of the octave! That is, if you start at

C4, you will end up with C5 and this is why it is called a circle. Not

only that, but every note you hit when playing the 5ths is a different note.

This means that the circle of fifths hits every note once and only once, a key

property useful for tuning the scale and for studying it mathematically.

c. Pythagorean, Equal, Meantone, and “Well” Temperaments¶

Historical developments are central to discussions of temperament because mathematics was no help; practical tuning algorithms could only be invented by the tuners of the time. Pythagoras is credited with inventing the Pythagorean Temperament at around 550 BC, in which the chromatic scale is generated by tuning in perfect 5ths, using the circle of fifths. Unfortunately, the twelve perfect 5ths in the circle of fifths do not make an exact factor of two. Therefore, the final note you get is not exactly the octave note but is too high in frequency by what is called the “Pythagorean comma”, about 23 cents (a cent is one hundredths of a semitone). Since a 4th plus a 5th make up an octave, the Pythagorean temperament results in a scale with perfect 4ths and 5ths, but the octave is dissonant. It turns out that tuning in perfect 5ths leaves the 3rds in bad shape, another disadvantage of the Pythagorean temperament. Now if we were to tune by contracting each 5th by 23/12 cents, we would end up with exactly one octave and that is one way of tuning an Equal Temperament (ET) scale. In fact, we shall use this method in the section on tuning (c. Equal Temperament (ET)). The ET scale was already known within a hundred years or so after invention of the Pythagorean temperament. Thus ET is not a “modern temperament” (a frequent misconception).

Following the introduction of the Pythagorean temperament, all newer temperaments were efforts at improving on it. The first method was to halve the Pythagorean comma by distributing it among two final 5ths. One major development was Meantone Temperament, in which the 3rds were made just (exact) instead of the 5ths. Musically, 3rds play more prominent roles than 5ths, so that meantone made sense, because during its heyday music made greater use of 3rds. Unfortunately, meantone has a wolf worse than Pythagorean.

The next milestone is represented by Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier in which music was written with “key color” in mind, which was a property of Well Temperaments (WT). These were non-ET temperaments that struck a compromise between meantone and Pythagorean. This concept worked because Pythagorean tuning ended up sharp, while meantone is flat (ET and WT give perfect octaves). In addition, WT presented the possibility of not only good 3rds, but also good 5ths. The simplest WT (to tune) was devised by Kirnberger, a student of Bach. But it has a terrible wolf. “Better” WTs (all temperaments are compromises and they all have advantages and disadvantages) were devised by Werckmeister and by Young (which is almost the same as Vallotti). If we broadly classify tunings as Meantone, WT, or Pythagorean, then ET is a WT because ET is neither sharp nor flat.

The violin takes advantage of its unique design to circumvent these temperament problems. The open strings make intervals of a 5th with each other, so that the violin naturally tunes Pythagorean (anyone can tune it!). Since the 3rds can always be fingered just (meaning exact), it has all the advantages of the Pythagorean, meantone, and WT, with no wolf in sight! In addition, it has a complete set of frequencies (infinite) within its frequency range. Little wonder that the violin is held in such high esteem by musicians.

Since about 1850, ET had been almost universally accepted because of its musical freedom and the trend towards increasing dissonance by composers. All the other temperaments are generically classified as “historical temperaments”, which is clearly a misnomer. Most WTs are relatively easy to tune, and most harpsichord owners had to tune their own instruments, which is why they used WT. This historical use of WT gave rise to the concept of key color in which each key, depending on the temperament, endowed specific colors to the music, mainly through the small de-tunings that create “tension” and other effects. After listening to music played on pianos tuned to WT, ET tends to sound muddy and bland. Thus key color does matter. On the other hand, there is always some kind of a wolf in the WTs which can be very annoying.

For playing most of the music composed around the times of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, WT works best. As an example, Beethoven chose intervals for the dissonant ninths in the first movement of his Moonlight Sonata that are less dissonant in WT. These great composers were acutely aware of temperament. You will see a dramatic demonstration of WT if you listen to the last movement of Beethoven’s Waldstein played in ET and WT. This movement is heavily pedaled, making harmony a major issue.

From Bach’s time to about Chopin’s time, tuners and composers seldom documented their tunings and we have precious little information on those tunings. At one time, in the early 1900s, it was believed that Bach used ET because, how else would he be able to write music in all the keys unless you could freely transpose from one to the other? Some writers even made the preposterous statement that Bach invented ET! Such arguments, and the fact that there was no “standard WT” to choose from, led to the acceptance of ET as the universal tuning used by tuners, to this day. Standardization to ET also assured tuners of a good career because ET was too difficult for anyone but well trained tuners to accurately tune.

As pianists became better informed and investigated the WTs, they re-discovered key color. In 1975, Herbert Anton Kellner concluded that Bach had written his music with key color in mind, and that Bach used a WT, not ET. But which WT? Kellner guessed at a WT which most tuners justifiably rejected as too speculative. Subsequent search concentrated on well known WTs such as Kirnberger, Werckmeister, and Young. They all produced key color but still left open the question of what Bach used. In 2004, Bradley Lehman proposed that the strange spirals at the top of the cover page of Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier manuscript represented a tuning diagram (see Larips.com), and used the diagram to produce a WT that is fairly close to Vallotti. Bach’s tunings were mainly for harpsichord and organ, since pianos as we know them today didn’t exist at that time. One requirement of harpsichord tuning is that it be simple enough so that it can be done in about 10 minutes on a familiar instrument, and Lehman’s Bach tuning met that criterion. Thus we now have a pretty good idea of what temperament Bach used.

If we decide to adopt WT instead of ET, which WT should we standardize to? Firstly, the differences between the “good” WTs are not as large as the differences between ET and most WTs, so practically any WT you pick would be an improvement. We do not need to pick a specific WT - we can specify the best WT for each piece we play; this option is practical only for electronic and self-tuning pianos that can switch temperaments easily. In order to intelligently pick the “best” WT, we must know what we are seeking in a WT. We seek: pure harmonies and key color. Unfortunately, we can not have both because they tend to be mutually exclusive. Pure harmony is an improvement over ET, but is not as sophisticated as key color. We will encounter this type of phenomenon in “stretch” (see j. What is Stretch?) whereby the music sounds better if the intervals are tuned slightly sharp. Unlike stretch, however, key color is created by dissonances associated with the Pythagorean comma. With this caveat, therefore, we should pick a WT with the best key color and least dissonance, which is Young. If you want to hear what a clear harmony sounds like, try Kirnberger, which has the largest number of just intervals.

We now see that picking a WT is not only a matter of solving the Pythagorean

comma, but also of gaining key color to enhance music – in a way, we are

creating something good from something bad. The price we pay is that composers

must learn key color, but they have naturally done so in the past. It is

certainly a joy to listen to music played in WT, but it is even more

fascinating to play music in WT. Chopin is somewhat of an enigma in this regard

because he loved the black keys and used keys far from “home” (home means near

C major, with few accidentals, as normally tuned). He probably considered

the black keys easier to play (once you learn FFP, b. Playing with Flat Fingers), so that the

fears many students feel when they see all those sharps and flats in Chopin’s

music is not justified. Chopin used one tuner who later committed suicide, and

there is no record of how he tuned. Who knows? Could it be that he tuned

Chopin’s piano to favor the black keys? Because of the “far out” keys he tended

to use, Chopin’s music benefits only slightly from WT, as normally tuned and

frequently hits WT wolves. Conclusions: We should get away from ET because of

the joy of playing on WT; if we must pick one WT, it should be Young;

otherwise, it is best to have a choice of WTs (as in electronic pianos); if you

want to hear pure harmonies, try Kirnberger. The WTs will teach us key color

which not only enhances the music, but also sharpens our sense of musicality.